AT CURTAIN:

GEORGE DUMMITT ’69 is sitting on the hood of a cream-colored American Motors Gremlin on the set of Hedwig and the Angry Inch at Broadway’s Belasco Theatre in New York City. He is wearing a Local One union T-shirt, blue jeans, work boots. A quick-link hangs from his belt and holds his keys. A photographer snaps pictures of GEORGE.

GEORGE

[Looking out toward the audience]

Sitting where I am right now in the theatre, I can absolutely see the direct line back to Oswego.

[PHOTOGRAPHER repositions GEORGE on the car and snaps more pictures.]

There’s no question in my mind that what I do for a living—where I find all this satisfaction—

goes right back to Oswego and the time that I spent in theatre there.[Special effects begin. Scene changes from the car at Belasco Theatre today, to a car in front of the 700 Building on SUNY Oswego Campus.]

GEORGE

[Looking out toward the audience]

So, I’m two years in the psychology program at Oswego, and on my 19th birthday,

Michael Berkman ’69, who is a friend, gives me the keys to his Bonneville.[GEORGE acknowledges MICHAEL, who addresses him.]

MICHAEL

Take it when you want it. Keep it in gas. Be careful. And let me know when you’re going

to take it.[GEORGE nods toward MICHAEL. Then turns back to the audience.]

GEORGE

One night I wanted to borrow the car so I went to find Michael at the 700 Building—the old theatre building before Waterman existed.

[GEORGE walks into the 700 Building. His jaw drops as he scans a 16-foot high Gothic arch

structure, with wrought iron fastenings on oak doors, marble steps and stained glass windows. Theatre Professor John Mincher stands to the side watching GEORGE’s reaction.]Oh wait, that’s made out of plywood, and it’s been painted, and it’s got canvas on it, and that’s some sort of gelatin for the colored glass. Well, this could be fun…

[END OF SCENE]

For George Dummitt ’69, that moment in the 700 Building in 1967 has driven him to a successful career as a carpenter and stagehand in the New York City theatre world. Spanning more than 40 years, his career has enabled him to transform the three bare walls of a theatre into new scenes and time periods for a wide range of characters—a 1930s New York City boxing ring for Joe Bonaparte in Golden Boy, an Elizabethan law court for an original practice version of Twelfth Night – Richard III, an Afghan war scene for a German transgender rock-n-roller in Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and a dozen other productions.

“I started to think about all the characters, all the events, all the situations that have happened within my space,” Dummitt says. “It all goes in and out the same loading door. It’s amazing what I do for a living.”

However, there has been one space that hasn’t changed much for Dummitt—a Paris opera house at the Majestic Theatre in New York City—at which the Phantom of the Opera has been running for 27 years. He began loading in the show in September 1987—four months before it opened—and he continues to work as a member of the carpenter department there when he isn’t working on assignment to another Shubert theatre.

“We all knew it would be a good job, but we didn’t know it would be like this,” Dummitt says of Phantom, which surpassed Cats as the longest-running Broadway show. “I certainly know Phantom as well as anybody. Now, I listen for my cues, and I listen when there’s a new person or an understudy. You can’t listen every night. You’d go crazy.”

In 1997, Dummitt became head carpenter for the Shubert Organization’s Lyceum Theatre, and later transferred into the Shubert’s Belasco Theatre as head carpenter, a role he currently holds. He oversees the members of the carpenter department at the Belasco during load-ins, production runs and load-outs of a show. Then when that theatre goes dark between shows, he returns to his position at Phantom.

During load-ins, Dummitt and his crew assemble set pieces envisioned by the set designer and built at union scenic shops. If needed, the carpenter crew can be called on to build additional scenic elements on site as required by the design. They collaborate with electricians, props staff, actors and directors and develop carpenter and stagehand cues for the production. He clocks long days during this part of a show: a week’s pay stub has been known to show 92 hours worked.

Once the show has opened, his schedule lightens, dropping to 32 to 36 hours a week, or about 4.5 hours for each of the seven to eight shows a week. He memorizes his cues, responds to the slight variations that occur in live performances and ensures that set movement, curtain drops and scene changes all go smoothly.

Eventually, his least favorite part of his job arrives.

“I hate the last performance because everything you do will be for the last time,” says Dummitt, who hopes to be retired before that day comes for Phantom. “The last time you move the set, the last time you open the door, the last time you drop the curtain. There’s such a finality.”

Then, it’s load-out. Dummitt and his crew strip the stage, again leaving three bare walls—an empty space for the next production to fill with new characters, sets and situations.

AT CURTAIN:

It’s 1969. GEORGE is wearing a graduation cap and gown and has just graduated from SUNY Oswego. He addresses the audience, answering the question about his future plans.

GEORGE

So I started going to “work parties” on Saturday mornings at the campus theatre. We’d build the scenery for an upcoming show on Wednesday nights and Saturday mornings. And I found a whole group of people who I really liked, and who liked what I was doing. It was the opening of a whole new way to go. But I still got my degree in psychology because that seemed like a good thing to do. I first thought that after graduation maybe I’ll go into the theatre. But, no. It’s way too risky a business. It won’t take care of my wife and children.

[GEORGE takes off the cap and gown, and the scene changes into a dormitory hallway at the University of Buffalo.]

Now, I’m working as a head resident advisor in Tower dorm as I earn my master’s in student personnel and counseling for higher education. I figure someday I’ll run student housing or a counseling center on a college campus. One day I’m walking down the hallway when…

[The lights flicker. GEORGE stares at the lights and freezes.]

VOICE OF REASON

George, what are you doing here? You have no wife. You have no children.

What are you doing here?GEORGE

I am on the Road to Damascus, as I like to think of it, and realize I was planning on people who didn’t exist. I am worried about providing for people who I didn’t have to care for yet. I finish my degree in counseling, because it never hurts to have a master’s in your pocket, and decide to give this theatre stuff a try.

[END OF SCENE]

The jump from a career in counseling to theatre wasn’t Dummitt’s first dramatic conversion. Raised Jewish, he became a Mennonite in seventh grade after attending some workshops and recreational programs sponsored by young Mennonite men who were doing alternative service in lieu of military service during the Vietnam War. The Mennonites taught Dummitt about ham radios and, more importantly, introduced him to the craft of carpentry.

His skills in woodworking and repairing things landed 16-year-old Dummitt a summer job as a carpenter at Manhattan General Hospital, where his mother worked as an administrative assistant. He decided he would study industrial arts at SUNY Oswego, which he says “was the industrial arts college at the time.” But the following summer—the summer before he came to Oswego, Dummitt transitioned from being a carpenter to a job in the drug addiction detox center at the hospital. The experience at the rehab center prompted him to write to Oswego and change his major from IA to psychology.

While he has never used his counseling and psychology degrees professionally, he says he probably draws on them every day.

Perhaps his counseling background helped him secure one of his most important roles in his life—that of a husband and father of four: Joanna, 35, working on a doctorate at UC Santa Cruz; David, 33, a speechwriter for Bloomberg Inc.; and 23-year-old identical twins, Jared, a research analyst at a New York City law firm who is applying to law schools, and Morgan, a professional sculptor.

He met his wife, Susan, during an opening night party for The Rink, starring Liza Minnelli and Chita Rivera. Susan, a social worker, attended the event as a guest of a good friend who worked at a fashion house that had a relationship with Minnelli.

“There’s no reason in the world we should have met—except that we were supposed to,” Dummitt says. “I said the five hardest words a man can say to a woman, ‘Would you like to dance.’ She said yes and I brought her home that night in a taxi with 50 balloons from the party trailing behind us. Three years later, we married.”

Throughout their marriage, the Dummitts have supported each other’s careers and interests. George helped raise awareness and support for AIDS—a career focus for Susan for many years—by representing Phantom in the annual AIDS Walk NY, participating in Broadway’s Annual Easter Bonnet Competition and offering backstage “Tours with George” in exchange for a donation that benefits an AIDS charity.

Susan, in turn, developed a tradition of giving George an opening night gift tailored to the show.

“She expends a certain amount of creative energy in pursuit of the opening night gift,” George says, with a smile. Among his favorites are the ruby red slippers and flying monkey T-shirt he received and wore during opening night of Over the Rainbow, a retelling of the last months of Judy Garland’s life, and a small stuffed buffalo with a one-year certificate of adoption of a wildlife buffalo for the opening of David Mamet’s American Buffalo.

AT CURTAIN:

Present day. GEORGE in his jeans and T-shirt stands on stage at Belasco, with fellow crew members, as they run through set, lighting and sound cues during pre-show. House manager STEPHANIE WALLIS approaches the stage from the house. GEORGE sees where she’s heading and calls out to her.

GEORGE

Careful, Stephanie. The stairs will be moving on the next cue.

[STEPHANIE adjusts her positioning, just as a set of stairs slides out from beneath the stage into the house.]

TECHNICAL CREW MEMBER

[To GEORGE, lightly]

So, they’re going to put you on the cover of a magazine? Wow, it must be a slow news day.

[Other crew members join in the good-natured heckling. GEORGE shakes his head and smiles.]

GEORGE

Yeah, I know, I know.

[END OF SCENE]

Within the Belasco Theatre, everyone knows Dummitt and Dummitt knows everyone. Within the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees Local One, the oldest and highly respected entertainment union in the country, Dummitt is also well-known.

“I represent 3,200 members, but I know George personally,” says James Claffey Jr., president of IATSE Local One. “He’s in the front row at every union meeting, and he mentors new members and gives them our history.”

Claffey recruited Dummitt to serve on the Broadway negotiating committee because he is “credible and well-respected with union employees as well as the employers on the other side of the table.”

In 2007, a Local One strike closed down Broadway for 19 days, and Dummitt came up with the “We are One” slogan and helped keep the members’ spirits up, Claffey says.

“He is a master carpenter, a great collaborator, and his work ethic is nothing short of excellent,” Claffey says. “We’re lucky to have him.”

Faculty and alumni of the Oswego theatre department share that sentiment as well.

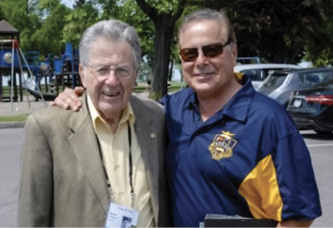

“I consider George to be the most important theatre alumnus Oswego has graduated,” says John Mincher, a retired technical theatre professor who helped found the department in the 1960s. “He is an amazing carpenter and a very caring person. He single-handedly established an annual breakfast reunion for technical and design alumni in New York City that evolved into the annual theatre reunion that is still held today. He set up backstage tours of Broadway theatres for our students and faculty, and he helped open doors for Oswego alumni.”

Dummitt has also established two endowed funds at Oswego: George Dummitt ’69 Resident Assistant Fund to support resident assistants with financial need and the George Dummitt ’69 Technical Theatre Fund, which enables the department to bring to campus high-profile theatre professionals to speak in classes and to purchase materials and equipment beyond what the shrinking state budget allows.

In addition to the funding, Theatre Professor Kitty Macey says Dummitt has contributed to the department in ways that no amount of funding could. He uses his personal connections to share his peers’ professional work with students and to help Oswego alumni get their foot in the door, which is often the hardest part of making it in New York.

“He is just an amazing man,” Macey says. “He has been instrumental in helping so many people do so many things. He is a very generous person. He goes out of his way to support his alma mater.”

Through Dummitt’s efforts, the Oswego theatre department has copies of all the blueprints and plans for the Broadway production of Big River and the costume “bible” for Golden Boy, including 2014 Tony nominated designer Catherine Zuber’s sketches, fabric swatches, photos from the fittings of each character, charts for dressers, everything that costume professionals in New York City would need to costume a show.

True to his backstage style, Dummitt is quick to redirect the attention.

“Oswego led me to this very fulfilling life,” he says. “I feel that I owe Oswego. When I’m presented with the opportunity, it’s my responsibility to give back.”

AT CURTAIN:

GEORGE stands off stage as the cast takes their bows at curtain call. The lead characters turn toward the wings and beckon GEORGE onto the stage. The cast separates to clear out center stage for GEORGE. He looks out into the audience to see generations of SUNY Oswego faculty, students and alumni giving him a well-deserved standing ovation.

[Curtain falls.]

— Story by Margaret Spillett. Photos by Jennifer Weisbord.

GEORGE DUMMITT

Height: 6’2”

Weight: 225 pounds

Hair: Silver gray

Eyes: Blue

Age: 66

Education: Bachelor’s in psychology, SUNY Oswego, 1969; master’s in student personnel and counseling for higher education, University of Buffalo, 1971

Role: Head carpenter

Venue: Belasco Theatre, Shubert Organization

Other Credits: SUNY Oswego Distinguished Alumnus Award, 1990; Commencement Eve Torchlight Speaker, 1992; George Dummitt ’69 Resident Assistant Fund; George Dummitt ’69

Technical Theatre Fund

Special Skills: Carpentry,

collaboration, leadership, philanthropy, mentoring

You might also like

More from Alumni Profiles

Astrophysicist, Yale Professor Credits Oswego with Setting His Course for Stellar Career

Astrophysicist, Yale Professor Credits Oswego with Setting His Course for Stellar Career Earl Bellinger ’12 is one stellar guy. A quick review …

BHI Alumnus from Liberia Gains World of Experience

BHI Alumnus from Liberia Gains World of Experience Otis Gbala M’23 became the first SUNY Oswego graduate who studied from Liberia …

Passion Drives Alumnus to Pursue Music, Arts Career

Passion Drives Alumnus to Pursue Music, Arts Career If you ever wanted to know how to make it in the arts, …

1 Comment

I worked with George at the Allenhurst dorm of the State University of New York at Buffalo. So many of the young men and women who worked in the dorms as resident advisors or head residents with me have gone on to to great work in their professions of choice. I’m so proud of the work George has done, fondly remember his International Harvester pick up named Ishmael, and wish him well on his life’s journey.