L’Affaire Cookware

It was the Fifties. Sort of. The calendar said 1962. A year later JFK’s assassination would provide the ultimate trigger event for a decade, the Sixties, whose memories will be lost when my generation moves on. But for the moment it was the Fifties. Like a tippler headed to somewhere over his limit, any decade takes a while to get going, and then helplessly staggers on past the end, to where its momentum runs out. Let’s face it, a lot of the grooviest Sixties stuff actually went down somewhere between ’70 and ’75, by which time nothing was groovy any more.

The town had a Revolutionary War fort, a power plant, and a remarkably high rate of unemployment. It was shaped by water—Lake Ontario on the North, fed by streams everywhere. The Oswego River cleaved the place right down the middle. History had been lived there and around there. Nothing spectacular, you understand, more along the lines of living out life’s drama. Speaking of which, there was a college, too.

The isolation alone was enough to put Oswego, New York, 1962, smack dab into the Fifties. That’s where I spent my college years, in limbo between Beatnik and Hippie, the former over-the-hill, the latter not yet making the scene. It was madras and chinos, not paisley and jeans. The juke box was stuffed with rock-and-roll—too early for unleavened rock. The outlaw writers were Kerouac and Salinger, with Baldwin and Kesey to come. A certain heavyweight champ was Cassius Clay. Love meant going steady, giving her your fraternity pin, early marriage—this was before it was free. Our guy was Presley, not Dylan, though the scraggly, scratchy would-be waif would be a welcome change-of-pace for the hippest among us, not too far off. The all-purpose escape route was beer, not pot, at least not where I was. It was the Fifties, any way you look at it, right there, right then, in the Sixties.

The calendar’s lag factor was compounded by the fact that life between cities along the Great Lakes is tolerable only because change, progress, whatever, creeps in when people aren’t looking—reality gets a late pass. Time didn’t quite stand still in those days, but it sure moved slow. My crowd’s outlook was rooted in our parents’ fresh memories of depression and war—back-to-back shots straight to the teeth of a whole generation, head-trip heirlooms passed on to us in real-time. From their experience we learned that a nickel was precious and an early, sudden death likely. Who knew something was missing? We were having a good enough time, there at the edge of our world—Oz, we called it with great relish. Short for Oswego, and other things—short for the lives we fancied we were living, or would live.

The shore of Lake Ontario, a great Great Lake, was home to the main campus, off to the side of town. Part of Oswego, but not really. An accommodation by all parties, I always figured. Other pieces of the college were scattered around the burg and beyond. The Hotel Pontiac, sagging and struggling like the rest of downtown, served as a men’s dorm during a brief growth spurt up the hill. A berth at The Pontiac came with a shuttle bus to the Student Union. And it had a bar. Pretty good deal, it seemed to me, bunking my frosh year in a three-storey

brick dorm at lakeside, where the wind turned cheeks cherry-red for the duration. Waist-high ropes along the paths kept us from disappearing into one of the half-dozen blizzards we slogged through each winter. We never wore white.

My pal Steve Wizeman, a zoo major in more ways than one, came up via the Hotel Pontiac, where he bunked with Heavy in a two-man room on the third floor his freshman year. They met while registering at the Pontiac, early September arrivals bound for first-year orientation. Wizeman quickly realized they were assigned to the same room. He looked the human beach ball up-and-down, and then back-and-forth. He stepped back, said, “Heavy,” and raced for the stairs, determined to claim the top bunk and save his life. He argued all year that Heavy, being heavy, should pay somewhere between sixty and seventy-five percent of the room charge, based on actual space occupied. It was one of many arguments he lost more than once.

During that first year Wizeman earned a reputation for quirkiness in the extreme. This quirkiness, as it turned out, was neither fueled nor inhibited by alcohol. Nonetheless, he spent considerable time his freshman year taking on fluids in the Hotel Pontiac bar. Sacagawea’s Hideaway was right inside the front door, open late, and dark enough that an accommodating bartender could credibly claim to have misread the birth date on a young man’s draft card.

There, in a manner somewhere beyond self-assured, Wizeman leaned back against the bar for his full first freshman semester, nightly as well as afternoonly. He seemed always to be accompanied by a handful of overachieving novices, learning to drink. Wizeman was more than full of himself; you could see him overflow as he regaled the gang with tales of snakes and scorpions, his fulsome brows atwitter and his broad grin a constant presence under light brown eyes. Although usually broke, Wizeman seldom ran dry of drink or words, or companions happy to supply the drink in order to hear the words.

Wizeman, however, wasn’t nearly as smart as he thought he was: A witness later reported that his face lost every drop of blood at the sight of his grades that first January. He didn’t see it coming—it was exactly the kind of blind spot that was gonna get him one day. Wizeman never said what his grades had been, but he did immediately and matter-of-factly announce that those who were interested should look for him on the Dean’s List at the end of the spring semester. Our boy then nearly disappeared until mid-May. Heavy said Wizeman slept less and snored more. Sightings were limited to the shuttle bus, campus pathways, and a back table in the library. He wasn’t unfriendly, curt, shitty, or aloof about it at all. He simply wasn’t available for the spring semester.

So it was. Fall semester was fun-time, the downhill side of the academic slope. Following his fuck-up half-year, Wizeman focused on survival. He spent late winters and early springs climbing a steep hill, making it, and then crowing relentlessly. His reward was a summer hiatus far from home, in a swamp or jungle somewhere tropical, handling slippery and sometimes dangerous creatures. One summer he hitchhiked all the way through Central America and back, working as an alligator handler in tourist traps and drinking tequila, a bottle a day, he said. He was no doubt a spectacle, a gringo among Latinos too polite to question or challenge his particular brand of loco. I always imagined him as the premier tourist attraction those years in Equatorial America, and asked him once if any postcards featured his wily grin. “Nope,” he said. “Not yet.”

Wizeman’s idyllic summers were followed each year by a return to school and an academic plummet so spectacular that his grade point average became the subject of some substantial bets around the Hotel Pontiac, even after he’d moved out. He managed to set the pace in two divergent directions, to distinguish himself as both a scholar and an idiot. He seemed to enjoy the thrill, the whole scene, although springtime must have been lonely.

Our second year at school found us hunkered down outside town in an old, running-down former inn, lately turned into the home of Beta Tau Epsilon. The Beta House was one of a handful of Greek outposts whose members lacked the wherewithal to own property in town. Call it the low-rent district; officially it was Fruit Valley. Farms around there, mostly, and, yes, the name inspired more than a few lame cracks from the homophobes—damn near everyone was scared of queers.

The local family produce farms were a too-tempting target for the frat guys down Highway 104. At least they were for the Beta men. More than one midnight requisition was filled in the fields and orchards, where apples, pears, potatoes, tomatoes, onions, you name it, were sacked, stacked, and ready for pick-up. There was a cadre of us with a dangerous combination of abundant nerve, a sense of not much to lose, and a streaky, self-justifying attitude of entitlement—enough of each ingredient to put us on the road late at night with an empty car trunk outbound, and, on return, a rear-end sagging nearly to the tire-tops.

The Fifties looked the other way. They acted like a locked house was a sign that you didn’t trust your neighbors, your community. Looking back, I know there were always mischiefmakers afoot. A little mistrust, a few locked doors, might have stood some people in good stead. And, too, a padlock might have kept a good friend among us.

The Beta House, of course, didn’t have locks; how to keep track of the key? As one of many notable residents, Wizeman, the reptile honcho, continued to be a reliable source of entertainment during fall semesters. Always leading with style, he kept a boa constrictor in his room at the house. Fed it a white rat every Wednesday evening, eight o’clock sharp, don’t miss it, it won’t come around again for another week. “Slinky”, the boa was called, and it certainly was. The rats got named too, before being eased into the cage. There was usually a small crowd wedged in for the viewing, and a front-row seat earned a shot at naming the dinner. Wizeman insisted the name be offered in a sentence so the crowd could fully appreciate the thought behind the last-minute moniker. “A La Carte” was one I remember, as in “Okay, Slinky, it’s dinner A La Carte for you this evening.” A more sophisticated crowd would have done that one al fresco, but it was winter, iced over as always, and there were so many other games to play after dark.

For example, consider the Sorority Crawl. A half-dozen of us knew how to get into, and out of, a few sorority houses by avenues more interesting and challenging, less obvious, than the front door. So, once in a while, a handful of stone-cold-sober guys would pick a house and, in the dead of night, get inside it. Strictly for thrills, you understand. The object was always to leave enough of a trail to spark a morning-time conversation, something along the lines of, “Do you know who turned the dining room chairs upside down?” Or, “Why is the phone off the hook?” Or, “What’s the coffee table doing in the kitchen sink?”

We focused a lot on not getting nabbed. No one was itching to wear Uncle Sam’s Army green or, worse, to spend the next few years earning a hardscrabble living while trying to get back into the school you never should have gotten your ass thrown out of in the first place. There was always some history major saying Vietnam was gonna be the next big thing. We didn’t necessarily buy that, but I’ll never forget B.K. leaning into my face before my first crawl, hissing, “Whatever you do, don’t get me caught—I’m not about to lose my student draft deferment. There’s guys dying in this world, and I have no interest whatsoever.” So, for the sake of brotherhood and survival, the crawls were kept very quiet, known only to the handful of us who went out now and again.

By the time of his junior year, the last winter he had to wear two pairs of socks to keep warm, Wizeman was going stronger than ever. Amid the autumn excitement that fed his inevitable winter ruination, my idiot friend was desperately trying to make his scattered ends meet. This led him to the job as part-time Kitchen Manager for the Brothers of Beta Tau Epsilon; it was a job none of the other guys was interested in that year, so we were glad to have a sure hand in the kitchen as long as he promised to keep his pets off the menu.

Our cook was Mrs. B. The “B” was for Benwell, a sad, sometimes motherly woman who no doubt had once been well, but who wasn’t any more. In addition to the usual stuff of life, she’d lost a husband and a son, both before their time—the son, a fraternity brother, had gone just after his graduation in a car wreck so bad the casket was closed. I know, I was there. It’s a story I’ll tell one day.

In the matter of their culinary endeavors, Mrs. B. and Wizeman were nominally each other’s boss. She did the cooking and made sure her favorites ate as their mothers would have them. He handled the money, dealt with vendors, helped out at mealtime, ran errands in Mrs. B.’s Chevy (side-trips were to be expected), and otherwise oversaw our getting fed. He ate last, but usually best.

Wizeman’s access to the Chevy was no small perk—cars in our set were scarce, and unreliable. Nothing ran as it should, especially during the endless winter. Most of us got by on hitch-hiking, bumming rides, shoe-leather express. There were a few established “hitching corners” around town. From there, you could get a ride from a student, a townie, a truck driver, a drunk, a housewife, as long as you were going their way. I myself could never stand still long enough for that deal—“hike while you hitch” was my motto.

The Beta kitchen was hurting in the hardware department the fall of Wizeman’s reign. The last pledge class had helped replace losses from severe kitchen breakage, and our shelves strained once again with glasses, plates, cups, bowls. Drawers were crammed with silverware. Most of the stuff looked a lot like it came from the campus dining hall, but questions were never asked. Wizeman’s problem was that we’d been unable to do anything about our clutter of aging pots and pans—the heavy artillery in Mrs. B.’s assault on young men’s hunger. The artillery was no longer heavy. It was thin, wrinkled, dimpled as only pot-bottoms can be, with some pieces missing handle bolts or handles entirely, and a couple looking like they’d recently been involved in an oil change. Wizeman was pushing for an investment, with Mrs. B. behind him all the way.

Dick Petworth, the cheapest President a fraternity ever had, refused to alter the budget or, worse, to put it to a vote, knowing that would only encourage the brothers to raise innumerable proposals for all kinds of nonsense. Petworth was a few years older, a guy who’d been to sea out in the Pacific, someone who knew to expect the unexpected. “I served in the United States Navy,” he said once, “And that’ll give you a little perspective, believe me.”

He never pulled those covers back any farther, except to say, “Take my word, gentlemen. There’s a lot of conflict in the world and we don’t need any more around here. So, keep a lid on it, let’s have a party that don’t get anybody killed, and everyone have a nice evening.” His Navy time had taught him a thing or two, he claimed, and he was right. He was getting through school on a mix of loans, GI Bill payments, Navy Reserve checks, and occasional work at a local watering hole. Our leader was a grown-up among boys. “Spanky”, we called him, after the bald kid on the Little Rascals.

Despite Spanky’s intransigence, the pots remained very much on Wizeman’s mind, which is exactly where Mrs. B. wanted them until some miracle or other occurred. The Kitchen Manager broached the subject to a few of us over stuffed pork chops, mashed potatoes, and succotash on an October Tuesday. “Look, fellas, Mrs. B. ain’t gonna let go ’til we get her some better equipment. And she’s right—that stuff’s crap. What would you say to a special tax on the Brothers who eat at the House? Ten bucks apiece should do it.” Lead balloon, right there.

B.K. filled the vacuum. “I gotta hit the books for awhile. Anyone goin’ out later?”

“How about some cards and an early-morning crawl?” This suggestion from Wizeman, still near the top of his autumn down-slope and itching to pick up a little speed. His temptations were persuasive, and that night four of us made our last crawl. Into the Theta House through the basement window, across the laundry room, where a lacy thing hanging from the rafters caught B.K.’s hat and he had to pull it away as if it were cobwebs. Up the stairs to the entrance hall, with the living room to the left and a powder room off to the side. On the right, the old dining room, now a sitting room but nonetheless still showing off an ornate chandelier—watch it, duck! Through there, the kitchen and a quick check of the fridge, which was never locked. None ever were in any of those houses. I always wondered if the sisters knew.

We’d been there plenty of times, officially and otherwise. Dates, meetings, study groups, attempted seductions—we’d done it all right there with the lights on, but now they were out. We were straining to see each other and any traps that might be waiting. I remembered the creak in the dining room floor, and waved the others around it. Smiling to myself, I knew that the morning would bring news from a Theta sister about an unnamed, slightly unstable housemate who went around in the middle of the night, moving the furniture to the most ludicrous spots.

As usual there was no plan for leaving our mark. We were in the kitchen and I was thinking about turning on a water faucet to about medium, not enough to make much sound. Let someone discover it in the morning. Hot or cold? As I decided on penny-saving cold, Wizeman leaned close into my face and leered, pointing upward to the ceiling pot rack. It bristled with pots, pans, lids, ladles. Not quite new, but very well taken care of, judging by what we could see in the dim glow.

Wizeman decided to take advantage of opportunity. He grabbed a handsome stew-pot and jammed it into my gut like it was a baby I was obliged to grasp. He pressed another on Snail, who’d never been on one of these jaunts, and who looked pretty scared. From there, Wizeman couldn’t be stopped from plunging ahead on one more downhill run, his blind spot in charge and his mind off-duty.

We left, arms full, clumsily, right out the front door; any other exit would have been too risky, although our route was foolhardy, no question. Our luck held for the moment, and we were away with a prize—many prizes—to quiet Mrs. B., increase our dining pleasure, and brighten our overall outlook on life.

And improve our outlook they did, for the short term—thirty-six hours, more or less. Wizeman displayed the haul in the center of our immense oval kitchen table, pyramid style, so as to catch even a sleepwalker’s immediate attention. It was three pots high—nearly a yard straight up—and three across at the base, plus pans leaning into the structure and lids up against those.

The aluminum sculpture looked like it might collapse if provoked in any way, and Mrs. B. froze at the sight when she came in the door at five in the morning. She slowly, carefully took off her coat and told herself Ronnie wouldn’t have been involved in such foolishness when he lived in this house. She froze at this thought, and at knowing any further movement would raise a clang and clatter to wake the whole house.

Wizeman had heard the Chevy pull in and squeak to a stop, his wake-up call. Moments later he showed up for breakfast duty, ready to go in cowboy boots, boxer shorts, his Camp Oswego T-shirt, and a badly dented bowler hat. He admired his pyramid, hoping for maybe a motherly hug, maybe a kiss on the cheek. Just a show of gratitude was all he wanted, or needed. He was disappointed, for she’d become accustomed to her space, her distance, and Mrs. B.’s emotional range tended more toward holding in than giving out, especially with the guys she liked most. And, anyhow, Wizeman wasn’t on that list, never had been—I figured it was something about the reptiles.

On this occasion, though, she gave Wizeman a bit of a twisted smile, and her eyes looked for a moment like there was someone in there. His grin grew surprisingly shy. It was a moment of solidarity, a connection, somehow, finally. Mrs. B. would ask no questions, and answer none, either. Wizeman quietly disassembled the pyramid, his grin growing as he pointedly handed over each dear gift. Finally he whispered, “Mission accomplished, Ma’am.” She smiled again.

I hadn’t been to bed yet, and caught this unlikely vignette while lingering in the doorway, not wanting to interrupt or, worse, to dislodge the sculpture. Soon brothers began to wander in, too sleepy, hungry, distracted to notice the new gear. But once someone commented, the curiosity meter popped way up.

Wizeman had a Wizeman answer. “Whaddya mean, new? These aren’t new. They’re the same pots been here all fall; you didn’t notice. Jeez, they’re not new, anyway. Came from some second-hand store, looks like. But they been right here all along. You just never saw ’em before. Obviously you’ve run out of more important things to think about!”

Some guys bought that. Some were cowed by the suggestion that they’d run out of meaty topics to ponder. A few were suspicious. Others were willing to suspend disbelief in the interest of harmony, or to avoid a risky subject. Those who knew the truth ducked the conversation—no point in taking credit; the brothers’ silent appreciation was enough. We were curious, though, about what had happened to the old stuff, gone sometime before the morning rush.

“Well, right now our retired cookware is caressing the back seat of a certain Chevy,” Wizeman replied when asked quietly over an extra cup of coffee. “What would be your suggestion for their next stop? I was thinking the lake, or maybe Bob’s Bargain Barn, though I hate to be greedy.

B.K. didn’t miss a beat. “My boy, whatever you do, get rid of our old friends—we don’t wanna be seen with two sets of stuff. We’re a little beyond mischief here—this ain’t a couple sacks of potatoes left out in a field overnight. Get rid of every last piece, and act like nothing happened—what we’ve got is what we’ve had all year.”

Wizeman’s day drifted on, to a point in the early afternoon when he couldn’t resist a trip to the Hotel Pontiac for a liquid interlude with some locals he’d befriended in his days as a resident. Predictably, they were hunched over the bar in Sacagawea’s Hideaway when Wizeman arrived around two-thirty. His plan was a quick beer, then on to the bogus errand at the A&P that had been his excuse for the trip in the first place.

One beer turned quickly to three as Wizeman won two coin flips for a round each. He couldn’t leave on a win streak; ever the optimist, he was reluctant to walk away while he was so far ahead. The other thing was that his gambling friends were fully capable of hurting a college boy who wasn’t all that physical, except around snakes. Wizeman, of course, was mostly oblivious to the second point, but instinct told him to stay until he bought a round. He was lucky to get away with only covering one round, by which time he had five beers under his belt. He escaped after offering up a shot to go with the beer, atonement of a sort. Wizeman had one foot out the door and was away before the others’ beers were half drained.

By now it was the local equivalent of rush hour, and the grocery checkout line was four housewives long at both counters. Running late and tapping his foot, Wizeman stood behind some seriously overflowing shopping carts. He fumbled a bit with his two-pound bag of spaghetti and it fell from his careless grip, a splat to the floor. As he’d hoped, this caught the ladies’ attention; he shrugged and feigned embarrassment, the real thing being well out of his emotional repertoire.

“Wouldn’t you know it?” Wizeman said, casting his eyes downward to the bag. “I come in here and buy only one thing. Here I am at the back of the line minding my own business, and I can’t even hold onto that one thing.” This was followed by his best sheepish smile and, no surprise, invitations from the head of both lines: “Here, jump in front of me—I’m gonna be forever!”

Wizeman obliged, and was back on the road, late but at least in motion. Up ahead he spotted what was sure to be another delay—a packed hitching corner, students waiting for rides somewhere out Route 104, just where he was headed. Couldn’t breeze by them—autumn was giving way to Oz’s early winter, and a serious chill was setting in. Even with darkness coming on, he’d be spotted and word would get around. Nuzzling the brake and pulling over to the corner, he saw a few Theta sisters in the front row under a streetlight. “Their lucky day,” he said to himself out loud. They’d have a ride right at their door, since the Beta House was a little further beyond Thetaland.

He remembered the stuff in the back too late. As he reached to unlock the passengerside doors, his mind flashed, bringing the first sensation of nausea. He froze at the colliding images bursting before him—the smiling sisters now reaching toward the door, the hardware in the back seat, his entire dismal future. His hand slapped the back-door lock down before it had unlatched, leaving a surprised look on the sister he’d locked out, her grip still on the handle and her eyes on the back seat. Wizeman turned to Trish Colombo, sliding in to take the suicide seat, right in the middle. He saw that Judy Neary would be riding shotgun, and feverishly shouted, “Tell them I can only take two! I can only take two! No room. No room.” Judy relayed the message, slammed the door, and they were off.

Sweaters and coats, along with armfuls of books, kept the girls from twisting around to see what was going on in the back seat, but they were curious. And they were put out. It looked like there was a lot of open space back there, and Wizeman had stiffed their friends, who’d now have to shiver a few extra minutes on the corner. The sisters curtly said thanks and dove into a conversation about the best nearby schools for student-teaching assignments. This left Wizeman on his own to ponder what further disaster lay ahead. He dropped the sisters off with a nearfalsetto, “Good to see ya both. Study hard!”

As they slid out, Wizeman thought he saw the girls try to sneak a peek into the back seat.

It was now dark and there wasn’t much to see—a reflection of the house lights, maybe, coming from the car floor, some round shapes on the seat. They slammed the door and he gunned the Chevy, sweating bullets, and wondering where this was headed.

After dinner, Wizeman transferred the booty to a borrowed car and did what he could as easily have done first thing that morning. He knew a spot where the water came in deep against a hillside, and it was there that he filled each pot with earth and stone, tied lids to handles, and heaved one pot at a time, straight out into Lake Ontario. As he drove away, he told himself this would all be a long-forgotten episode, long forgotten, by graduation next year.

That wasn’t in the cards. Very early the next morning, President Dick Petworth got a phone call from Dr. Nicolas Rustini, the closest thing we had to any form of adult supervision, our Faculty Advisor. The “advisor” part was a joke, but he was on the faculty—abnormal psychology, didn’t it figure? A wisp of a man. We invited him to every party; he always came alone, got quietly drunk early, and excused himself before anything very interesting happened. In the present instance, however, all bets were off, since his call concerned the matter of a few

missing pots and pans.

Dr. R. said he’d had a visit to the dean’s office, where he learned there’d been a burglary at the Theta Chi Rho sorority house two nights back; the kitchen pot rack had been stripped clean. He noted that Wizeman had been seen driving around with a bunch of pots and pans, seen by some Theta sisters who got a quick look into the back seat as they were left waiting on a corner in town. They said they saw enough to know that Wizeman’s cargo wasn’t theirs, but they were convinced the pots in the Chevy had something to do with their own missing

cookware.

Dr. R. acknowledged it was all circumstantial, so far. He asked about bringing the Chief of the Campus Police around to have a little talk with a couple of the brothers. He wondered, “Could he, maybe, have a look at what you’re using these days to get yourselves fed?”

You don’t say no to questions like that. Spanky understood. His parsimony, his seriousness, his utter unhipness, and his ability to relate to adults—he was one, after all—made him an unlikely, but fortunate, choice to lead our particular outfit. He knew trouble when he saw it, and right now it was real close, staring him in the face, yelling in his ear. He angled for time, got an hour, and had a quick confab with the few guys whose opinions he trusted at all, plus a couple of officers he was duty-bound to include. I was there ex officio, Secretary that year, but

probably would have been anyway—Spanky found me entertaining, if not always sufficiently self-disciplined. It was seven guys, plus Wizeman, invited as an “interested party”.

Spanky laid it out straight. “Here’s the situation, guys. The Theta girls got their kitchen stuff stolen. A day later some of them saw our old pots in the Chevy when Wizeman stopped at the hitching corner near campus. Too much coincidence, if you know what I mean. Dr. R. wants to stop by and check out the kitchen. Wants to bring a friend from the campus fuzz. I’m thinking we should ’fess up, drive the pots straight to the Theta House, right now, and get whatever credit we can for being honest, even if it is a tad after-the-fact. We say it started as a

joke but got outta hand. We reenlist the old pots and hope the dean lets us slide, no harm done. Speaking of which, Wizeman, where’s the stuff you had in the Chevy?”

Wizeman’s eyes rolled upward. He squinted, bringing his brushy brows together. His peepers disappeared. “Well, Brothers, they’re gone. Funny thing. A little late, I admit, but definitely gone. Unrecoverable, in a watery grave sorta way. I guess I’m front-and-center on this one.” He was getting used to the idea, the main shock having been borne behind the steering wheel, right next to a couple of Theta girls, the evening before.

After some to-and-fro, we agreed Spanky would tell Dr. R. the pots were on the way home. He’d say the joke obviously went too far. Our sincere apologies. We’d like to make it up to the fair sisters any way our esteemed Advisor and beneficent Dean might suggest.

I’m confident Spanky represented us as well as anyone could have, but it didn’t work. What it came down to was that Dr. R., didn’t have any spine at all. Amazing he could stand up. That had always served our interests in the past, but not this time. To be fair, he didn’t have anything at all to work with when it came to our reputation. But he did cave quickly all the same. The word came back to President Petworth directly from the Dean of Students: First, he wanted to see Wizeman in an hour. Fully dressed, please. Second, he wanted to help the brothers of Beta Tau Epsilon more fully appreciate their responsibilities to the community and the college. We should expect a year on social probation. The single hope for consideration would entail other guilty parties coming forward.

The only thing to do was call a special meeting—get all the brothers clued in and hear what they had to say. This amounted to fifty-five guys sitting around the edges of the granitefloored dining room, with chairs and tables scattered along three bare walls. The bar was pushed up against the fourth wall and fronted by a long table and chairs for six officers facing their brothers. An announced start time of seven o’clock sharp guaranteed we’d have a quorum somewhere around seven-thirty, which is about when we got going.

The rule was, no drinking at meetings. Before and after were up to you. In other words, all bets were off, and it was up to Spanky to keep order. The Parliamentarian, Joey Cicerone, was as usual at the edge of his seat, Roberts’ Rules within close reach. The presence of this eager beaver, and the order he was so anxious to maintain, were welcome only to a few, and then chiefly as a foil, the butt of the joke, a target big enough to hit and small enough to bring down.

Spanky opened the meeting with a summary of our predicament, which by this time was a surprise to no one at all. “Fellas, we got a situation,” he started, the sailor coming up out of him as he spoke. His rosy cheeks glowed brighter than usual. “Somehow we wound up with somebody else’s pots and pans hanging in our kitchen. We’ll never know how that happened. I understand they have found their way back home.” He paused. “Now, meanwhile, our old stuff was seen, strictly by coincidence, in the back seat of Mrs. B.’s car, with our good brother

Wizeman at the wheel. This aroused suspicions, which led to fact-finding, which led to trouble.”

With the room calm and all eyes on him, Wizeman looked around, forcing a smile. “Evening, Brothers.”

Spanky continued, “Our favorite dean has tossed Wizeman’s ass.” He looked straight at Wizeman. “Sorry ‘bout that, Stevie.” Then, to the murmuring crowd, he said, “And, of course, he’s looking for Beta to pay a price, too. He’s talking social probation for a year—all the usual conditions, including a grade average of two-point-five-zero if we wanna get back to house parties and other mission-critical activities. But he’s willing to cut us some slack, in trade for more of our own flesh. The son-of-a-bitch.” He took a quick beat, then looked at me. “Strike

that last phrase.”

The murmuring bubbled over. “Wizeman, you’re gone? He actually threw you out for that? I thought the pots went back yesterday.”

“That wasn’t theft—it was an accident. How can they boot someone for that?”

“Who’s gonna feed us? Can Wizeman still be Kitchen Manager?”

“Whaddya gonna do, Wizeman?”

From the corner, John Louie, the biggest and blondest man in the room, interrupted the overlapping questions with one of his own, “Did you say the dean is willing to negotiate? Does that mean there’s a way out?”

This quieted the room, and Spanky answered in his calmest voice. “John Louie, let’s take one thing at a time. First our brother, then the dean.” He turned to Wizeman. “You probably shouldn’t even be in this meeting, Babycakes—I don’t know the rules on that.” He was careful not to see Joey’s waving hand. “But you’re here. What did the dean have to say, if you don’t mind?”

Wizeman shrugged. “Didn’t take long. He knew some things about me. That time mooning the Greyhound bus. Other stuff. My academic record is a little unconvincing, he said. Can you believe that, ‘unconvincing’? I’m on the fucking Dean’s List—his fucking list—half the fucking time! Blah, blah, blah, something about my general comportment and reputation. Plus, I wouldn’t back off when he wanted me to name names. ‘My only accomplice is the devil,’ I told him.”

I could feel the muscles in my neck unwind. He continued. “I’m out for a year, maybe more, unless I become a congressman, or a saint or something, and then try to get back in. I’ll be happy to never see that son-of-a-bitch again. You guys, on the other hand, I will miss. Maybe I’ll sneak back for a party from time-to-time.”

“Speaking of parties, how do we get out from under this probation bullshit,” John Louie asked again, leaning over the inch-thick spindles of the oak dining chair he had straddled backwards.

“The dean is really, really serious about this,” Spanky answered. “He says it’s obvious Wizeman couldn’t have done the deed alone and he’s curious about who else was in on it. He’s willing to reconsider the social probation if other names come to his attention. We’re down to the nitty-gritty, Brothers.”

“What now,” someone asked.

“I dunno,” Wizeman said. “I’ll probably join the Army, see the world. Maybe I can get in the Special Forces, get some quiet time in a swamp or jungle someplace.”

“No, I mean what about us?”

With nothing to lose, Wizeman spoke first, “Why go on a witch hunt just so some bullshit dean can get his rocks off? I’m your guy on this one.”

“Yeah, but who wants to go on social pro?”

“Sounds like we could negotiate for a little slack,” John Louie threw in, “A coupla brothers might be willing to make a small sacrifice, confess an honest boy’s mistake, help keep this outfit viable. The dean will appreciate someone ’fessin’ up a hell of a lot more than having to catch ’em. He’d go easy on someone man enough to step up.”

John Louie spoke for a handful of hard-liners destined for exciting but ultimately miserable lives. He declared a moral and legal stance, insisting on the fraternity’s god-given right to exist, its right to support life in a house, its right to tap a few kegs and go crazy on a Saturday night. Never mind academic records, good citizen awards, bullshit, bullshit, bullshit. The beer-gut crowd cheered when Moose summed up their position, “We ain’t a fraternity if we can’t throw parties amusing enough to cause a little stir! The cops don’t come, it ain’t a party!”

But they peaked too early. Judd Wesley, our oldest brother at twenty-five, took Moose on, straight up. “So, Moose, you’re saying we oughta encourage anyone who was in on Wizeman’s little caper to turn themselves over? That assumes there was anyone else, which I myself can’t buy. But you’d be willing to give up our—your—brothers for the sake of a few parties?”

“Aw, don’t put it that way. It sounds so crass.” Moose sounded hurt.

Father Wesley looked straight at Moose, then scanned the room. “The truth can be crass, my rather large friend. I’m just pointing it out to you. We gain nothing by pushing this. We lose our souls if we give up our brothers to some shithead dean. There’s lotsa bars out along the lake, and they’re empty most Saturday nights. They’d be glad to see a bunch of us roll in with a serious bout of drinking in mind and maybe a few dates who ain’t so bad to look at. Economics, Brothers, economics. And morals. And integrity.”

“I agree.” Joey was still at the edge of his seat. “Not about the party stuff, but about morals and integrity.” He was drowned out by laughter, hoots, and a couple of New Years’ noisemakers.

The Father ignored Joey. “Look, fellas, it’s not like we ain’t been here before. I’ve personally survived three extended episodes of social probation. They’ve got our number, no lie. They been watchin’ us since I’ve been here—and this is my fourth year as a senior!”

Dink, serving his second term as Treasurer, put up two cents. “Gentlemen, let’s think about this rationally, from a business point of view. Dues are our only source of income, and we’re always short. We’ve got to grow to survive. Instead, we had a small pledge class again last year. Now we’ve lost Wizeman’s dues and may lose some others. We have got to increase our appeal to the freshmen, which is hard to do when you’re practically in jail. We can’t afford social pro!”

Joey, still wrestling to get the floor, jumped back in, “Yeah, without a good pledge class we could go broke. We could disappear. Imagine a world without Beta Tau Epsilon. What about our legacy?”

“Chicken shit.” John Louie said what I was thinking.

This cued the Deacon, an inaptly named senior. “Stuff the legacy crap, Joey. We been on social probation before—the Father holds the school record, for chrissakes. We got used to it like you get used to drinkin’ warm beer when there ain’t cold, right, Father? We had great pledge classes—look at the guys in this room. Most of us are bastard children of social pro. And I wouldn’t wanna be in this room with anybody who ain’t here.”

Joey was getting more excited. “We’ve gotta get right with the dean on this. We’re a social fraternity, not an anti-social fraternity! This could be our chance to prove we’re honorable men, turn this thing around, you know?” The fact that Joey got a quiet burst of agreement from pockets around the room was disturbing; I hadn’t realized so many self-righteous moralistic bastards had been snuck into the fraternity. The gooey sentiment was depressing. But the implications were plain unsettling.

My perspective had never been pure, and the things I was hearing took it to the edge. The names in question were the subject of unsurprisingly accurate speculation, and a few of us had smoked an extra pack or two the last couple days. The dean was after blood, some of it mine. Wizeman had taken a direct hit. I hated to see him out there on his own, but social pro was starting to look pretty good. Wizeman was a loner to his core, always, and no stranger to a tight spot. Throwing in with him now was pointless. Better to lie low and hope my brothers-in-crime did too. Wizeman could be counted on, whether it was in his best interest or not. Some of the other brothers were hardly a sure thing.

I shoulda figured someone would put me on the spot sooner or later, but I was preoccupied, focused on the sensation of being sucked down a drain. I wasn’t ready when it came from John Louie himself. “Satch, Mr. Secretary, you’ve been awful quiet. You usually have something to say on the important topics. You’re the big picture guy. Whaddya think, wouldn’t it be nice to have an active fraternity next year?”

“John Louie, I can’t think of anything I’d like more,” I answered, telling myself to be careful. “It’ll be my senior year, for crissake. What kind of question is that? My opinion can’t be that big a deal.”

“And?” John Louie wasn’t going to give it up.

“I’d like us to be in business. Who wouldn’t? Well, maybe the dean, I give you that. But like The Father said, we’ve been on the edge of trouble since anyone can remember. We could get social pro on general principles alone, any time. Our reputation is shitty and our grades are worse. By the way, we owe Wizeman a thank-you for all those A’s last semester—they brought our average way up.” That got Wizeman to smile, finally. He was pleased, I’m sure, that I didn’t mention the effect of his first-semester grades.

“Now, on the subject of the hour, John Louie, suppose some guys said, ‘It’s me.’ Suppose they get thrown out of school. Suppose they get drafted. Mercy is not this dean’s style. This is his chance to send a message; he’d like a little extra raw meat but it won’t make any difference. We’re cooked either way, with or without turning on each other.”

“Don’t you think it’s worth a shot, Satch?” John Louie was now pissing me off.

“Look, John Louie, you want the big picture? Try this on for size: When I hear what’s been said tonight, I can’t believe some of my brothers think social pro is the end of the world just because we’d have to get a little creative about our recreational activities. Meanwhile, others of my brothers figure staying off probation is somehow gonna get Beta in good with the dean, about which who gives a shit anyway? Both of you are ready to hand over the culprits, wash your hands, and get on with life. Where’s the guarantee we wouldn’t get screwed even then? Social pro is my poison of choice.” There, I’d declared a preference for survival over outrageous parties and self-righteous moralism—at least that’s how I explained it to myself. I still wonder how the other guys saw it, or see it now, or would see it if they stopped to think.

The split was about even and I was hoping for a quick vote to get it over with. Then a coconspirator, an impossibly dispassionate B.K., leaned forward and maybe went too far.

“They’ve got their fuckin’ pots back,” he started. “What’s the difference now? Wizeman’s ass is the price. Sorry, boy, but you got caught, plain as day. I’m gonna miss you and the snakes, Wizeman, honest, but your fate is set. I don’t see any point in someone else getting thrown out of school. Remember, brothers, the draft awaits, and it could be any one of us another day. Nobody in this room is driven snow. Almost nobody, I guess, is more accurate.”

Wizeman smiled, both thumbs pointing to the smoke-stained ceiling. “Couldna said it better myself. Don’t worry ’bout me. I’m headed for a brighter future. No more deans, books, or bullshit. Look for me under that green beret. I’ll get some medals, get some girls, get some beers. I’ll have one or two of each for you boys.”

Spanky had been taking it all in and decided the time was right. “Gentlemen, this fraternity, this institution, is built on one thing: Brotherhood. Not the money, the parties, the girls, not even the stellar reputation we imagine somewhere way, way, way off in our future. But one thing: Brotherhood. Whatever integrity we have, we’ve gotta extend it to each other. That’s why I’m in this fraternity, and not in some fancy asshole house downtown.”

He had the room’s attention. “Here’s our choice: One, we strongly encourage some few brothers to come forward and bail us out. That would likely render them boot-camp-bound, not a pretty sight for them or whatever hell-hole they wound up in. The fraternity, meanwhile, might be free to exercise its rights until the next crisis comes along. Probably not that far off, if history tells the future. Second, we can circle the wagons, protect our brothers, and face the consequences, which will be gruesome, but manageable.”

“Now, I ask myself, which of these shitty little choices will most help our institution? What will keep us together, strong, and ready for official parties again when the time comes? Making sacrificial lambs of my brothers won’t do that, gentlemen. It would tear us apart. We might never heal. I say we hang together now, to party another day, to redeem ourselves in the eyes of His Deanship some other time in the future. Brotherhood, Brothers. Brotherhood.”

The room was more still than I’d ever seen it in any circumstances. Joey of course knew what had to be done. “Anyone want to call the question,” he asked quietly.

“Yeah, I’ll do that. Let’s see who’s got what between his legs.” John Louie was confident.

“I’ll second. And I’m hoping for a little maturity on this vote.” This came from The Owl, whose main interest was getting it over and heading out for a few brews. He was my best friend, but I never figured out if he was kidding about maturity.

Spanky slipped back into his official role. “All right, let’s vote. Joey, paper for everyone—one sheet per, no more under any circumstances.” Joey leapt up, itchy with authority. He’d already counted out fifty-five sheets, making sure.

“This will be a private ballot,” Spanky continued. “Two choices: Number One, we tell the dean we’ve investigated and found that Mr. Wizeman acted alone. Number Two, we assume there are some guilty parties. If they fail to come forward by noon tomorrow, we’ll search for them, find them, and give them to the dean.” Joey was at the board writing the choices out as Spanky spoke.

Clearly back in command, our leader asked, “Everybody got it? All you have to do is write down a number ‘one’ or ‘two’. That’s it. No editorial comments, please.”

There was a flurry of activity, paper being passed around and guys searching pockets and elsewhere for something they might put to paper. Students sans pen or pencil. But pretty good guys anyway, I decided as I watched, trying to settle my stomach by thinking favorably of those who were right then deciding my future. Meanwhile, one’s and two’s got written down and Joey collected them in a pith helmet loaned by The Snail.

Joey counted the votes at the officers’ table, with the other officers paying close attention. I felt a little light-headed as the outcome became clear to our small circle at the front of the room. My hopeful assessment had come true. We were off the griddle. On the down side, I was gonna have to face mid-term exams after all.

Once the count was agreed, Spanky made the announcement. “Brotherhood has prevailed, Brothers,” he began. “The vote is in favor of Number One. Wizeman is the dean’s only catch this time.”

“What? How could that be? What’s the vote count?” John Louie wasn’t ready to let go.

“You lost big-time, John Louie. Forty-six to nine. A pretty decisive vote, Brothers, considering the level of excitement we’ve had here tonight. Is there anyone who has any questions?” He waited. “As brothers, you know that unity is important. Any word to outsiders that’s not in line with our decision is gonna get you kicked straight out the door.” Spanky wanted to make sure that last point was understood, and looked straight at the core of the hardcore. “Everybody got it? I wanna hear anything anybody’s got to say right now.”

Moose and John Louie looked at each other and shrugged, their eyebrows mimicking the motion. Only Moose spoke. “Okay, okay, Mr. President. We’ll go along. Let’s call it unanimous, what the hell. I say let’s cast our good will on the Silver Lake Tavern this Saturday. May as well get started on the new routine.”

Tucked into his usual spot by the door, The Owl had become increasingly aware of what he referred to as his Great Thirst. “All right, we got that over. Move we adjourn. Any seconds?”

“Hang on a sec, Owl,” Spanky said. “We’ve got one more item of business. It has to do with eating, so listen up, everyone.” He paused, then went on, “The great, funny, sad, shitty part of this adventure is that it leaves us without any pots or pans. The kitchen is bare and if we wanna eat, it better get re-supplied. We got no budget whatsoever.” As he spoke, a few guys who weren’t on the meal plan slipped out a side door. “The only way I can see is a tax on the brothers who eat at the house—that’s twenty-eight guys. Ten bucks per is two-eighty, plenty to cover it. And rebates to all if we can do it for less. Whaddya say, guys?”

“What about using the party budget? We’re not gonna need that now.” Joey was all at once practical, naïve, unimaginative, and stupid.

Spanky frowned as if he’d been hoping that idea wouldn’t come up. “Good question, Joey. We’ll keep most of it as a reserve, just in case. You never know. The rest goes back to the brothers. We’re gonna need that refund for Silver Lake this weekend. Now, what about the ten dollars from the meal-plan guys for the kitchen stuff?”

“Okay, let’s do it. Anyone against? Move we adjourn. Any seconds?” The Owl had one foot out the door. Someone’s “Second” was buried under a chorus of whoops, much scraping of chairs, and the sounds of young men going out into the night.

Wizeman figured he better scram soon so as to deprive the dean of any excuse to press his point with the Brothers of Beta Tau Epsilon. That meant a quick, impromptu good-bye party the next night at Dirty Sam’s, an upstairs dive featuring ten-cent drafts in cloudy water glasses. It was a classic townie joint of the sort we descended upon from time-to-time. The Beta brothers were welcome as long as we kept the regulars’ glasses from going dry and didn’t break too much.

That party cost me a sure “C” in Biology, and it was worth it. John Louie, powerfully strong when sober, bent a solid iron bar around his neck early in the evening, and then was too drunk to bend it back later. Toejam passed out, face down, on the lap of Moose’s girlfriend and got carried, dead asleep, downstairs to the laundromat, where Moose stuffed him in a clothes dryer, inserted a dime, slammed the door, and hit the start button. Toejam was awake before the brothers who’d tagged along could stop laughing long enough to help him. Had to knock it open with his knee, he groused later. Back upstairs, someone stole the March of Dimes donation can from the end of the bar. But there were no secrets: The Snail bought his beers with nickels, dimes, and lots of pennies, all through the farewell. It was that kind of night, perfect for saying good-bye.

I took Wizeman aside at some point and tried to convince him he’d be back in a year. He was beyond hearing it, already getting on with the next round. “I’m gonna serve my country,” he said sloppily, “Special Forces, that’s fer me. Green Berets. John Wayne. Gung-ho. Bring it on!” He was gone next morning by the time I woke and realized I’d missed Biology Lab again.

The first postcard arrived the week after Thanksgiving. “Boot camp is a bitch, and I love her!” That’s all he wrote, and all he needed to. My Wizeman couldn’t possibly be buying the macho army propaganda on the front of the postcard, but he’d enjoy being dressed up in fatigues, playing at war. I was a little miffed that he’d addressed the card to “Satchmo and His Brothers” and told myself not to read too much into that. They were his brothers too. “Once a brother, always a brother.” We said that often enough that no one ever finished the line.

There was nothing more until late winter, and then two cards in rapid succession. The first showed a panorama of a Special Forces training camp. Wizeman had drawn himself in atop a tent, with both arms raised, middle fingers extending above his head in a cross-bones salute. No one in the post office noticed, I guessed. The message read, “Dined on water moccasin today. Tastes like shoe leather, get it?”

He’d covered over the picture on the second card with black ink. His message went right to the point: “Special Forces is special, but not that special!” Still no return address, so there was no way to get back to him.

By that time we were well into the spring semester, the season of Wizeman’s resurrection, his greatest triumphs. I guessed he would get some leave sooner or later and hoped he’d show up one day, that loopy look on his face and a beer in hand. Instead, there was another card in mid-March. “I’ve never been scared in a swamp before,” it said. That got to me, bad. Hard. The photo was a Saigon street scene. Vaguely French architecture. Mopeds, bicycles, vendors. Slender Asians of modest height, minding their own business. Not a westerner in sight, but I knew Wizeman was there, probably up to his bushy eyebrows in trouble.

The last card said it all: “Concerning War, Sherman was right.” Again he had covered the photo with black. The caption on the back said, “The beauty of Viet Nam is surpassed only by the friendliness of its people. In this typical scene, village children perform traditional dances for an audience of European tourists.” I guessed that wasn’t a scene Wizeman was making.

I remember feeling guilty about springtime in Oswego when I thought about Wizeman and his postcards, and so avoided those thoughts until May, when it occurred to me that he had no way of knowing my summer address. There hadn’t been a card in two months and I knew that was it. Still, I wanted to try for one more. I decided to make a side-trip while heading to my summer resort job, and paid a visit to Wizeman’s thoroughly unremarkable hometown right in the center of New York State. I knew his family lived on Maiden Lane, since it had been the butt of a joke we’d tossed back and forth during our time together. From there it wasn’t hard to find his parents, safely at home on a mid-May evening.

I explained my visit to a startled couple who’d never laid eyes on me before and who made it clear they’d just as soon it had never happened. “What’s up with Steve,” I asked. “I haven’t heard from him in awhile and I don’t think he’d know how to find me over the summer.”

“Well, you’ve got us topped, young man. He went through here real quick after he got thrown out of school. What a waste.” Wizeman’s dad was doing the talking, his mom looking on, and it wasn’t real cordial. They had less news than I did and weren’t too curious, either. I backed off that porch knowing Stevie’s leave-taking, from the very same spot, must have hurt really bad.

Now, looking back, I know Wizeman came through it okay, though there wasn’t the proof I would have liked. I was in Washington much, much later and looked for him on the wall. Nope. He’s not among the known dead. I think of him still when I see rattlesnake offered on an upscale menu. I think of him as I drive by a swamp in the mid-Atlantic, or on vacation in the Everglades, maybe Costa Rica. He comes to mind at the oddest times, always when the subject of Viet Nam comes up, but also when I find myself in the heavy artillery section of a kitchen

store. Wizeman’s trip into the jungle wasn’t his first disappearing act. I make myself believe it was his one last joke on us all.

More from Uncategorized

Find the Founder! – Winter 2024

Find the Founder - Winter 2024 In the Winter 2023 Issue, the Sheldon statue can be found in the top left …

Fun From Reunion Weekend

Fun From Reunion Weekend More than 550 alumni from 61 different class years ranging from 1962 through 2023 returned to the …

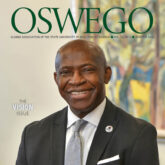

From the President

From the President Dear Members of the Laker Community, It is my great honor to introduce myself to you in this, my …

Leave A Reply

[…] Read a longer version of this column, L’Affaire Cookware. […]