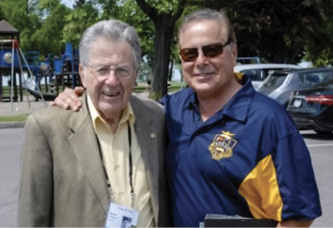

Wesley Brown ’68. Photo: Dan Kapp

The following is an excerpt from an essay that was included in the anthology How Dare We Write: A Multicultural Creative Writing Discourse (Modern History Press, May 2017).

I could tell you something,” my father said to me, beginning when I was seven or eight. He not only could but he did, especially after he’d had a few drinks. He told me stories from his childhood and youth that at times were harrowing, but never ceased to hold my attention. One could argue that it was inappropriate to be told, at such a young age, that my enslaved great-grandmother’s thumb was permanently splayed out by her master using a straight razor to slice it open whenever she did something not to his liking. There was nothing I could do but listen to him who, for whatever reasons, chose to unburden himself to me with these unsettling stories from his past.

The opening line of Joan Didion’s book, The White Album, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” crystalized how important it was for my father to tell those stories and by extension how indispensable it was for me to discover the stories I needed to tell. And I found many of them through trips to the South to visit relatives, as well as images of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and early 1960s.

My gradual move toward a more direct encounter with risk and danger arrived in June of 1965. I’d made the decision to go South to work on voter registration after two ‘Snick’ (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) staff workers spoke at the SUNY Oswego campus where I was a student. Their visit occurred during the same period of the assassination of Malcolm X and the Selma to Montgomery march.

I don’t doubt that my parents admired the courage of the young people putting themselves in harm’s way. However, they were not prepared for me being one of them. Perhaps, my father expected his stories would’ve been a warning that the world was a frighteningly unpredictable and dangerous place, and that I should not, needlessly, put myself in the way of its wrath. These were among the reasons why my parents left the South. And here I was determined to move closer to the site of the hurt and dangers they had fled.

The months I spent in Mississippi were life changing, forcing me to see myself and the world I inhabited in ways I could not have imagined. I was in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, helping to register black people who had been denied the right to vote in a country that was sending young men, many of whom were black, 10,000 miles away to bring democracy to Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Nothing I read or heard in the mainstream media reported this perspective or the entrenched economic, educational and political institutions that kept rural blacks in a condition of penury not that far removed from their circumstances after the Civil War.

Once I arrived at the view that the narrative emerging from my young life was one that had to involve putting myself into a movement to change the glaring disparities between what America promised and what it practiced, it became clear that I could not, in good conscience, serve in the Armed Forces of the United States. Perhaps, without knowing it, my Mississippi experiences and my determination to make common cause with others, wanting to create a story of our lives where we had a lot more to say about its direction, were the early indications that writing might be a way for me to find my own way in the world, rather than allow those embodying the diction of the powerful to do it for me.

Wesley Brown ’68 is a visiting faculty member in social studies and the arts at Bard College at Simon’s Rock in Great Barrington, Mass., and a professor emeritus of English at Rutgers University, where he taught for 26 years. He is the author of three novels, as well as three produced plays. He is the co-editor of a fiction multicultural anthology Imagining America and a nonfiction multicultural anthology Visions of America, and he is editor of The Teachers & Writers Guide to Frederick Douglass.

After leaving Mississippi, applying for and being refused conscientious objector status, graduating from college and becoming involved with the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s, I decided to make a serious commitment to write and found two mentors in Sonia Sanchez and John Oliver Killens whose writing workshops at the Countee Cullen Library in Harlem and Columbia University provided me with an invaluably supportive group of young black writers who challenged and encouraged one another.

My refusal to report for induction into the army in 1968 was never far from my mind. And in January, 1972, I was sentenced to three years in a federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

Dostoyevsky wrote in “Notes from the House of the Dead,” that if you want to grasp the nature of any so called civilized society, you need only to look at its prisons. Even from the relative safety of my minimum security facility, I found nothing to dispute Dostoyevsky’s assessment. All of the hierarchies, ethnic and racial group hostilities and the reliance on violence as the instrument of social control were present in a more extreme form.

I worked on a novel while incarcerated that had nothing to do with my experience in prison. After my release in 1973, a writer friend chastised me for not incorporating my time in prison into my autobiographical coming of age story of a young black man. Initially, I was reluctant to consider this, thinking it was still too raw in my mind to do justice to the experiences. However, after more thought, I had to acknowledge I really didn’t want to enter the emotional mine field I knew was waiting for me.

I asked myself why my father had passed on to me all those terrible stories? Remembering something Toni Morrison once said provided a possible answer: Coming to terms with a deep hurt, often, requires not keeping our distance but moving closer to it. So with more than a little trepidation, I wrote my way through emotions I hadn’t allowed myself to feel while in prison and my first novel was all the better for it. In every story or novel I’ve written since then I’ve tried to remember my father’s need to repeat his stories to me. That has given me the courage to write stories I’m reluctant to tell, making it not as likely that I’ll be at the mercy of the historical and personal hurt that claims us all.

—Wesley Brown ’68

You might also like

More from Class Notes

Class Notes – Winter 2024

Class Notes - Winter 2024 Editor’s Note: Due to changes to our typical production schedule, this Class Notes reflects submissions from July …

From the Archives – Winter 2024

From the Archives - Winter 2024 SAVE THE DATE: April 8, 2024 Oswego will experience a very rare total eclipse of the …

Oswego Matters – Winter 2024

Oswego Matters - Winter 2024 As a mother of two young children, I’ve grown accustomed to frequent transitions; to new beginnings; …