SUNY Oswego’s zoology program is thrust into the spotlight when alumna Allysa Swilley ’15 attains internet fame as April the giraffe’s zookeeper; program leads to careers from caregiver to researcher to conservationist to animal rescuer—and much more.

Photo: Matt Cummins

It’s just days after the season’s grand opening of Animal Adventure Park in Harpursville, N.Y., and Allysa Swilley ’15 is hard at work, both as its head zookeeper and its internet superstar.

Swilley has taken an unexpected encounter with international fame in stride, despite being watched for months by millions of fans via live webcam as she cared for the world’s most famous giraffe. April the giraffe captivated viewers around the world—1.25 million people were watching at the moment she gave birth to baby Tajiri on April 15 and a total of 232 million tuned in at some point during the live webcast. Now it’s a month later among the rolling hills and spring-green fields of the rural southern tier of New York, and Swilley, who grew up working on her grandfather’s dairy farm in Mehoopany, Pa., has just spent the previous week helping to prepare the small animal park for an onslaught of giraffe fans: On day three of the 2017 season, they’ve already come from as far as California.

“I’ve always known I wanted to work with animals,” Swilley said, as the day’s guests to the park greet her by name. While visitors are in a hurry to see the giraffes—including Oliver, Taj’s father—there’s no shortage of requests for photos of the giraffe’s caregiver, capturing her broad smile, signature blonde French braid, animal tattoos, rhinoceros necklace and Timberland work boots.

While the world watched, Swilley was often seen in the giraffe enclosures, providing care. What the world didn’t see: The long nights she spent alone in the giraffe barn sleeping on an army cot next to her giraffes (not very comfortable, she jokes), or how she watched the birth from just a few feet away, gripping the steel enclosure bars with both hands and “screaming internally because I was so excited … but I had to keep quiet so she wouldn’t get stressed.”

Swilley took a zoology class in high school that shaped her future.

“I knew that was it, for me,” she said. “I visited schools that offered zoology, and Oswego just felt like home.”

Not Your Typical Desk Job

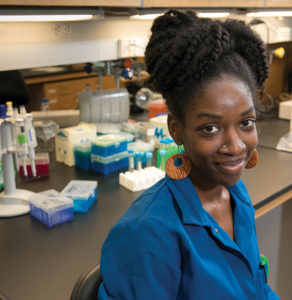

ANIMAL FACTS THAT AMAZE THE ZOOLOGISTS: Janet Charray Buckner ’11—“Some animal species, like west African frogs, can change gender when there is a lack of males or females in the population.” Photo: Reed Hutchinson

While some zoologists go to work in direct daily care of animals, others opt for research, including Janet Charray Buckner ’11, a doctoral candidate in the University of California—Los Angeles (UCLA) Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. But as Buckner can attest, zoological research is far from “hands off.”

Buckner was awarded a prestigious Fulbright fellowship, which took her to the Brazilian Amazon. There, she was stung by a bullet ant (one of the animal kingdom’s most painful stings), nearly stepped on a pit viper resting on a forest trail and “the best thing that happened on that trip—coming face to face with a mountain lion,” the primate phylogenetics researcher said.

Animal encounters that might cause the faint of heart to be overcome with fear are those that shape a zoologist’s career. And for Buckner, whose research interests include comparative genetics, trait evolution and biogeography of mammals and birds, it’s a bonus that you get to hang out with monkeys, peccaries, guans, frogs, snakes and coatis, not a deterrent.

“I chose zoology because I have been obsessed with nature and science since I was a little kid,” Buckner said. “I could not imagine doing anything else for a career.”

SUNY Oswego’s zoology program provides research opportunities for undergraduates—something often saved for graduate-level students at other institutions, she said.

“That experience was invaluable in my pursuit of a graduate degree, and I give much credit to my undergraduate education and mentors for my current success,” said Buckner, who studied population genetics and reproductive ecology of the endangered Bog Buckmoth with Dr. Karen Sime, Dr. Eric Hellquist and Dr. Amy Welsh during her time at SUNY Oswego.

“Learning how to walk in the bogs and fens without falling waist deep in water was a fun process,” Buckner said. “It is one of my most vivid memories from undergrad.”

Research opportunities for zoologists aren’t limited to just studying the living; just ask Dr. Frank Varriale ’97.

Dr. Varriale, a vertebrate paleontologist, earned a master’s in paleontology from South Dakota School of Mines and Technology and a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in the university’s Center for Functional Anatomy and Evolution. He was awarded the Alfred Sherwood Romer Prize from the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology for his research that resulted in a key discovery about the evolution of chewing in horned dinosaurs (ceratopsians). His research was the first to identify the unique chewing style of the plant-eating dinosaur Leptoceratops.

ANIMAL FACTS THAT AMAZE THE ZOOLOGISTS:

Dr. Frank Varriale ’97—“The recurrent laryngeal nerve in humans descends into the chest and loops around the heart back up the neck to innervate the voice box. The indirect route stems from our evolutionary ancestry when the heart of our fishy relatives was in the neck near the gills.”

“Much of our understanding of behavior, biology and function of dinosaurs comes from comparison of

extinct animals with living close relatives, making zoology an excellent place to start when trying to build a foundation of knowledge on which to study extinct animals,” said Dr. Varriale, who selected SUNY Oswego in no small part because it was the only SUNY offering a bachelor’s degree in zoology.

Dr. Varriale’s discovery of jaw mechanics, published in 2016, was the result of extensive travel (including to such places as Mongolia) and culminated in a “eureka moment” using scanning electron microscopy. The finding sent the scientist dashing up from the basement through the halls of Hopkins Medical School to share with a colleague. Dr. Varriale attributes his success to research strategies first practiced at SUNY Oswego, including a specific zoology course for which students sampled largemouth bass in a pond, standing in the mucky, murky water as they used nets to gather fish.

“I remember coming out of it covered from head to toe in pond weeds and mud, but thinking the battle cry ‘For Science!’” Dr. Varriale said. “It was the first time in my career that I felt like I was doing science, and felt the joy of collecting data for the purpose of revealing new insights.”

Read the Online Exclusive interview with Dr. Varriale

Zoology: A Rare Species of College Program

Not only is SUNY Oswego’s zoology program a program unlike its peers, it has very few peers to begin with. Fewer still are programs that offer undergraduate courses in specialized areas of zoological study.

While many colleges have opted to place zoology under a collective umbrella of biological science, SUNY Oswego has kept it as a separate field of study. Although it maintains an interdisciplinary relationship with biology, having its own identity has its perks, said Dr. Jennifer Olori, a graduate of Cornell University who teaches a variety of SUNY Oswego’s zoology courses, as well as serving as a zoology faculty adviser.

“It provides us with recognition as a unique program,” Dr. Olori said of the major that was first introduced at the college in 1975.

“It provides us with recognition as a unique program,” Dr. Olori said of the major that was first introduced at the college in 1975.

And with recognition comes not only the students who seek the niche, but the faculty who offer extremely specialized classes such as medical entomology, aquatic entomology, comparative anatomy, animal physiology, animal development, parasitology, mycology and wildlife techniques. Zoology students rub elbows in many courses with biology majors; faculty is shared.

“We really offer the full set of courses that have disappeared at other institutions,” she said.

Zoology includes a variety of career options that range from caregivers to conducting lab-based disease studies—and many, many offshoots. A zoologist may work in labs or the outdoors; generally, there are four areas of specialization: amphibians/reptiles, ichthyology (study of fish), mammals and birds. And at SUNY Oswego, the number of students who are majoring in the field has grown, from 169 in fall 2011 to 233 in fall 2016.

Dr. James MacKenzie, professor and chair of Biological Sciences, said the program attracts students from not only New York State and the northeast, but also from across the country.

“As the only zoology program in the SUNY system, we attract spectacular students,” he said.

SUNY Oswego maintains an extensive research and teaching collection—taxidermied fish from 1960 and a frog from 1910, anyone?

Dr. Diann Jackson M’88 at Rice Creek, has been updating the collection, checking its health and cataloging the content. The vertebrate and invertebrate teaching collections not only provide a method for students to take a course in invertebrates or even entomology—unheard of except at major universities—they also provide a method to leave a legacy, as the collection is constantly being updated by today’s students and faculty.

Zoology 387 classmates in the spring of 2017; Corrine Monaco ’18, Alyssa Lopez ’18 and Joel Barnett ’18 swab a frog found on the Rice Creek Field Station grounds.

But while the collections are … well, dead, Rice Creek itself is a 400-acre laboratory of living animals for research. And according to Dr. Olori, research appeals to many students—even those who may have initially been drawn to zoology because they wanted to cuddle a cute mammal.

Like the other STEM majors, zoology majors are using the state-of-the-art facilities at the Shineman Center. “They are using the molecular labs, DNA extraction equipment and the confocal microscope,” she said. “They are also going outside with waders and a net, because sometimes that’s the equipment you need.”

Jamal Lavine ’16 and Anthony Macchiano ’17 measure an amphibian found on the Rice Creek Field Station grounds.

Because of the niche nature of the major, alumni play a vital role in helping students get their feet in the door for careers. That’s because while jobs in zoology may seem hard to get, those who are landing them are those with the kind of research and training provided at SUNY Oswego, Olori said.

Oswego Biological Sciences Department Prepares Tomorrow’s Researchers

Online Exclusive:

Oswego Biological Sciences Department Prepares Tomorrow’s Researchers

A delicate salamander tattoo on the forearm of SUNY Oswego Professor Dr. Jennifer Olori captures a passion shared with her students: the study of amphibians.

Since 2012, Dr. Olori, collaborator Dr. Sofia Windstam and the Department of Biological Sciences have worked with 50 to 60 SUNY Oswego students annually on a project to study local amphibians. Hear about it here: http://wrvo.org/post/frog-wranglers.

The research was born from the understanding that in tropical areas, populations of frogs and salamanders have declined or even gone extinct, Dr. Olori said. Some causes might be climate change and loss of places for them to live, but disease is a cause as well. And, frogs and other amphibians are important indicators of ecosystem health, she said.

“It’s an opportunity to study what’s in our backyard and apply it to a larger scope,” Dr. Olori said of the study that is now in its sixth season of data collection – and is one of the few studies in New York State entirely focused on emerging diseases in native species of amphibians.

“What really makes our [research] stand out is that we have long-term data,” Dr. Olori said. “Most disease studies are done for a season or two, or across many locations. We’re monitoring the same population of frogs year after year.”

The research goals are to monitor local populations of frogs and salamanders and track the prevalence of invasive organisms such as chytrid fungus and Ranavirus, which are known to infect frogs. These data can be studied for other interactions that range from weather to climate to any predisposition for secondary infection, Dr. Olori said.

Dr. Olori, a graduate of Cornell University, is a member of the biological sciences faculty at SUNY Oswego and has published research on limb regeneration, skeletal growth and comparative skull morphology, to name a few areas.

Dr. Olori’s amphibian research at SUNY Oswego has helped students launch their own careers and pursue other research opportunities, using the skills learned as an undergraduate.

“It’s our department’s goal to maintain resources that make Oswego students job- and research-ready when they graduate,” she said.

Voice of Preservation

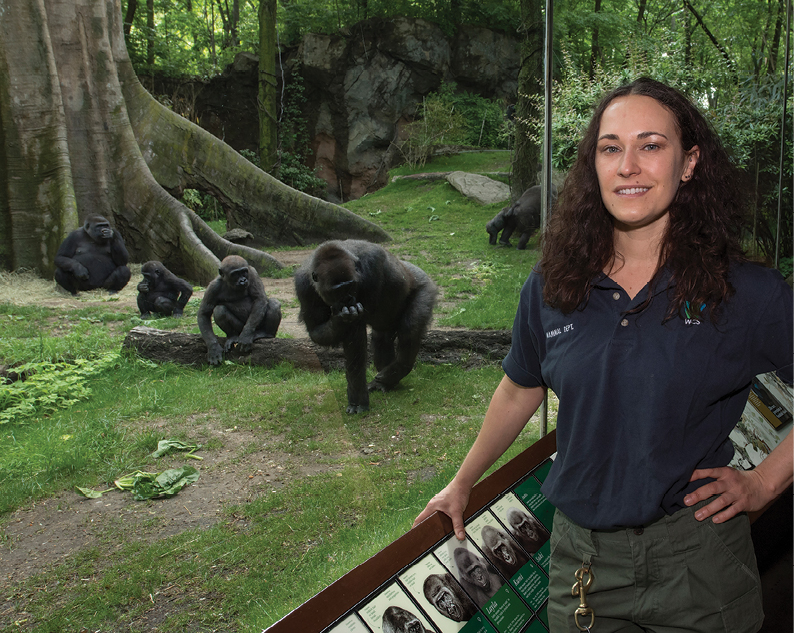

ANIMAL FACTS THAT AMAZE THE ZOOLOGISTS: Sabrina Squillari ’01— “Primates communicate verbally, visually and olfactorily. I love the sound of gorillas grumbling. That is a sign that they are happy and it is music to my ears.”

Insights aligned with a zoology frame of mind also can lead into careers dedicated to conservation.

Sabrina Squillari ’01 has worked for the Wildlife Conservation Society for 16 years and now is senior wild animal keeper in the Bronx Zoo’s Mammal Department, where she manages the Congo Gorilla Forest.

“I am proud to be part of an organization that has such a profound commitment to protecting the world’s wildlife and wild places,” Squillari said. “As special as the animals are to us, they also serve as ambassadors for their wild counterparts by inspiring zoo visitors to take an interest in conservation.”

Squillari provides specialized daily care for a visually impaired silverback gorilla.

“It has provided me with a sense of great purpose,” she said, of working to maintain quality of life and independence for not just him, but a troop of four, 11-year-old bachelor gorillas.

“We work weekends, holidays, sleep over in extreme weather and go to any length to make sure they are safe and secure at all times,” said Squillari, who grew up in New York City and was a frequent visitor to the Bronx Zoo as a child. She has continued her education at Columbia University and Hunter College, but credits SUNY Oswego with providing her with the academic and hands-on internships to allow her to quickly excel in the field.

ANIMAL FACTS THAT AMAZE THE ZOOLOGISTS: Emily McCormack ’99—“There is still not a federal law against private ownership of exotic animals in the U.S. A tiger, lion or a bear are wild animals that cannot be domesticated.”

Going to any length to secure safety and quality of life for animals is something Emily McCormack ’99 knows well.

McCormack is an animal curator and internship director at Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge in Eureka Springs, Ark., where she cares for exotic animals, including more than 100 big cats and bears. The organization rescues animals in dire straits—often at the hands of human incompetence.

“Participating in exotic animal rescue is very emotionally challenging,” McCormack said. “When we arrive at a rescue situation, you see a tiger or a bear for instance, in fear. These animals are amazing predators that have been put into horrible, abusive situations. My favorite part of my job is saving them and changing their fear into trust. We give them as much freedom as possible in a captive environment.”

McCormack was part of the team that completed the largest exotic animal rescue ever in U.S. history, through collaboration with 14 facilities to save and place 115 animals.

“We rescued three white tiger cubs who could not walk due to severe metabolic bone disease,” McCormack said. “This was caused from the lack of proper diet. They can now run and play. So, another favorite part of my job is healing the animals from their abuse.”

McCormack, who grew up in Oswego, had no idea of the insurmountable problems that big cats faced in the United States when she was a child dreaming of lions and tigers and bears.

“I have now been working rescuing exotic cats for 18 years,” she said. “I wouldn’t be where I am today without receiving my zoology degree at Oswego.”

It’s a Wild Life

Back at the animal park in Harpursville, giraffes Taj and April greet human guests, who stand on a deck alongside the giraffe enclosure: April is gently taking carrots from outstretched palms, her purplish tongue brushing against delighted children. Taj dozes in the safety of his mother’s shadow. The zoology program’s Alison Bickert ’15—who also works at the park, although for only a few weeks, and intern Olivia Wilmot ’18 are helping out, too.

“Oswego is practically running the place,” Swilley joked.

And to Swilley and her team, the park is home to much more than an internet sensation. Swilley strides through the park greeting the animals. There’s Gracie the monkey and Zuri the spotted hyena (bottlefed by Swilley, now full grown), kangaroos and macaws and wolves—some that she calls “sweetie” and “baby” as their ears perk in recognition of her voice.

But among the largest is the famous April, who closely follows Swilley’s movements through a crowd of visitors.

“It’s because we are family,” Swilley said of the giraffe’s attentiveness. Swilley, like many zoology majors at SUNY Oswego, interned abroad at animal preservation and conservation sanctuaries. She spent months at Transfrontier Africa in Balule Nature Reserve, South Africa, working with white rhinos and promoting conservation of African wildlife.

ANIMAL FACTS THAT AMAZE THE ZOOLOGISTS: Allysa Swilley ’15— “We’ve lost 40 percent of the world’s giraffes in the last 30 years.” Photo: Matt Cummins

And while Swilley enthusiastically welcomes her human fans to the animal park—she’s using the chance to launch educational efforts on endangered species and to encourage young people, especially girls, to enter STEM fields—her favorite time of day at the park is closing time.

“It’s the time of day that I can touch base with the animals on a very personal level,” she said.

Read a Q&A session with Allysa

More from Featured Content

Vision for the Future

VISION for the Future Peter O. Nwosu began his tenure as the 11th president of SUNY Oswego, building on the solid …

Envisioning the Potential in All Students

ENVISIONING the Potential in All Students Educator donates $2 million in recognition of his Oswego education, in support of future teachers Frank …

A Vision of Support

A VISION of Support Award-winning principal makes an impact on her school through her positivity and commitment When Nicole Knapp Ey ’02 …