In the beginning, there was a single teletype machine spitting out National Weather Service reports in SUNY Oswego’s Piez Hall.

There were students and professors gathered around pieces of paper, working out complicated mathematical equations using raw meteorological data to develop weather forecasts—with a pencil.

“There just wasn’t much available in the way of tools,” said Howard Shapiro ’74, laughing. “We really were the early pioneers.”

Read more from Shapiro and other alumni meteorologists in Wicked Weather: Meteorology Alumni Recall Oswego Weather.

Shapiro, who was among the first to graduate with a SUNY Oswego meteorology degree, recalls the first students of the program trudging around taking snow depth measurements, in an era of limited ability to gauge the current regional weather status—never mind forecast it.

“One time, I was on the phone with the National Weather Service out of Syracuse,” Shapiro said. “They had no idea Oswego was getting pounded with snow.”

This was before modern geostationary weather satellites even existed, Shapiro explained. The available data wasn’t sophisticated enough for them to see what was happening some 35 miles away.

Now, more than 40 years later, times—and technology—have changed. The presence of state-of-the-art equipment, with huge advances in the accumulation of knowledge, has set the science of meteorology on a path of rapid growth. And from the days of a few program pioneers, to today with an enrollment of 90, SUNY Oswego students are at the forefront of the field, as part of one of the largest undergraduate meteorology programs in New York and one that attracts students from throughout the Northeast.

The Influence of a Great Lake

From left are meteorology majors Lauren Cutler ’17, North Canton, Ohio; Alec Zuch ’17, Yorktown Heights, N.Y.; Lucy Bergemann ’17, Westwood, Mass.; and Christina Reis ’16, Buffalo, N.Y. They practice creating a weather forecast in the Shineman Center’s Meteorology Broadcasting Lab.

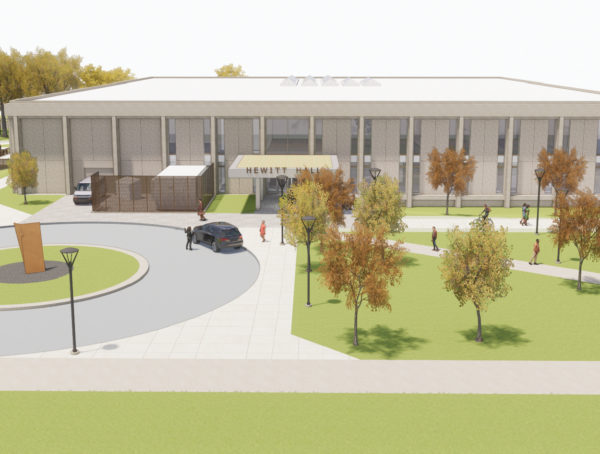

The SUNY Oswego Atmospheric and Geologic Sciences program, home of the meteorology students, is no longer housed in Piez Hall, which was replaced in 2013 with the $118 million Richard S. Shineman Center for Science, Engineering and Innovation. The program now boasts multiple observation decks, national funding, research credentials and modern equipment.

According to Dr. Alfred Stamm, who joined the department in 1977, today’s students have access to high-powered computers and current data designed for forecast modeling and weather prediction. There’s a new wind tunnel simulation area to test wind instruments and simulate flow around objects. There are two towers with weather instruments to keep track

of and archive current weather: wind, temperature, humidity, visibility, precipitation and solar radiation.

There are also instruments to measure cloud heights and wind from 50 to 400 meters above the Earth’s surface.

“We can find temperature, humidity pressure and wind with our radiosonde system, which carries sensors aloft using balloons,” Dr. Stamm said. “The sensors get the wind using global positioning software and all of the data is transmitted to our ground station. We can also measure weather parameters with a tethered balloon.Via the Internet, we get data from around the world and predictions from many different models worldwide.”

In other words, it’s come a long way since the teletype machine.

But there’s another fundamental factor that has been present as a backdrop to these astounding developments in meteorologic technology: Lake Ontario. For all students, past and present, it has been a bonding force in

their experiences at SUNY Oswego, and it’s been drawing aspiring weather students since the inception of a meteorology major in 1971.

According to Dr. Stamm, a campus perched on the eastern edge of the Great Lakes System—with its capability of churning up powerhouse snow storms and waterspouts—gets the blood pumping in the meteorology department and propels students on to careers, including broadcast meteorology worldwide and a wide range of positions with the National Weather Service.

“Storms come from the west, off the lake,” Dr. Stamm said. “It gives us lots of

snow, lightning and waterspouts, which is exciting weather to observe.”

And today’s students couldn’t agree more.

“I grew to love lake-effect snow back home in Buffalo, and Oswego’s proximity to Lake Ontario not only lets me experience its own brand of lake-effect snow, but also allows me to learn how to forecast it and conduct research,” said Christina Reis ’16, who is a dual meteorology and broadcasting major and chief meteorologist at SUNY Oswego’s WTOP-10. “The opportunities are growing each year, in both the broadcasting and meteorology departments, so I am able to get plenty of hands-on experience in both fields.”

The forecasting lab faces the lake so students can watch storms approach. The deck and observation room look both north and west. And while a cutting-edge facility on a Great Lake that spans 7,320 square miles—larger than the entire state of Connecticut—may draw students here, some

opt to leave classrooms and get into the elements farther afield.

Each year, a team of students travels to Kansas as part of a Storm Chasers program. Other research initiatives have gotten students out of the classroom, including one staffed largely by undergraduate students: the OWLeS (Ontario Winter Lake-effect Systems) program. SUNY Oswego received National Science Foundation funding to fly and drive into the heart of lake-effect snowstorms to study their structure and improve forecasting.

A Community in Search of Advancement

On the heels of moving into its new space in Shineman, the meteorology department’s growth has not slowed. It hired its first climatologist, Michael Veres, who started in the Fall 2015 semester. Veres plans to broaden students’ training to include knowledge of climate dynamics, with coursework dedicated to practical computer modeling and data analysis.

Dr. Veres said he joined SUNY Oswego following the completion of his doctoral studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln because of the opportunities for growth within a strong department.

“The advanced technology allows students and faculty to perform research and further our understanding of climatology,” said Dr. Veres.

A global viewpoint will only advance students’ understanding of the weather, Dr. Veres said.

Like all sciences, meteorological advances evolve in cadence with the times and the technological advances available to its students. Reflecting on this evolution—from his time on the Oswego lakeshore to his retirement home in Sun City, Ariz., where he now lives with his wife, Gail Lehrich Shapiro ’74, Shapiro is full of admiration.

“What the students have today compared to what we had, it’s just amazing,” said Shapiro, who spent 35 years as a meteorologist for WTVT-13 in Tampa, Fla.

It was a job he landed because he had a tape of himself standing in a tiny room in Oswego’s TelePrompTer cable TV offices.

Shapiro would walk downtown to stand in front of the single camera in his parka and deliver the forecast for city residents.

No graphics, no computer modeling. Just him.

You might also like

More from Fall/Winter 2015

Meteorology Alumni: New York to New Zealand

Meteorology Alumni: New York to New Zealand Christopher Brandolino ’96 has swapped hemispheres for a meteorology job, more than once. The SUNY …

Oz to LA: Oswego Students Get Inside Look At Entertainment

The sprawling metropolis of Los Angeles is probably most known for Hollywood, the section that is home to the entertainment …

Oz to LA: The Road From Campus to Cali

According to a 2013 study by the University of Southern California, Los Angeles has “shifted from a place of transplants …