I loved Dr. Edward A. Sheldon for his sympathic [sic] encouragement. In his relations to students he was as democratic as Abraham Lincoln. Hanging in my office over my desk is a life-size portrait of Dr. Sheldon. As I enter this room and look into his face he seems to say, “Good morning, Mr. Ferris.” —Woodbridge N. Ferris 1873

Woodbridge N. Ferris

If ever there was a young man whose prospects for doing great things with his life were dim, it was Woodbridge Ferris. He was born to Stella and John Ferris Jr. on January 6, 1853, near Spencer, N.Y. In the mid-19th century, Spencer was considered part of the frontier and Ferris was literally born in a log cabin, the first of seven children. His great grandfather, Richard Ferris, was a veteran of the Revolutionary War who lived in Scarsdale, and spent the entire War for Independence as part of the New York militia patrolling Westchester County. Pvt. Ferris saw no action during the war, but as a veteran, he was entitled to land in western New York state as payment for his war-time service.

Woodbridge was fortunate to have parents who — despite their own lack of formal education — wanted him to receive some school. As Ferris recalled, “On a spring morning when I was four years of age, father walked with me to the rural schoolhouse, a distance of about one half mile. During the eight succeeding years, school was the horror of my life.” This was, no doubt, partly due to bullying by the older boys and partly due to his treatment by his teacher.

It is not surprising, given his family background, that Ferris’ verbal skills were weak. His teacher in the one-room schoolhouse would call him a “blockhead” when he struggled with his lessons, an experience he remembered the rest of his life, and in a perverse way may have contributed to his later interest in teaching. By age 10 Ferris could read aloud “fairly well” and one of his household duties was to read the weekly newspaper stories of the Civil War to his father.

Ferris recalled that the winter he was 12 years of age marked what he called the turning point in his school life. William Holdridge, a teacher who lived in the district, invited the arithmetic class to visit his home evenings. “His personal encouragement aroused in me a hunger for knowledge, a desire to do something and be something.” He also related a vivid recollection of another influential event:

At the age of thirteen, I decided that if father ever paroled me from “serving time” in the district school I would on receiving that parole declare my school education finished. [However,]… a seemingly trifling event occurred near the approach of my fourteenth birthday. I was sent on an errand to our nearest neighbor. I found the woman of the house overhauling an ancient district school library. My eye caught sight of a small volume entitled the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. I was granted the loan of this book. I read this book, in fact this is the first book that I ever really read. I enjoyed every page, I was thrilled, I was awakened, I was inspired. I said to myself, “why can’t I do something worth while?”

And thus, the boy who hated school and who had planned to end his formal education as soon as he could, took a fateful step and at age 14 enrolled in the Spencer Academy for a nine-month term. At age 16, Ferris decided to attend a teachers’ institute at Waverly, conducted by Dr. John French, who was recognized by the State of New York for “his wonderful educational ability by utilizing his services in teachers’ institutes for many years.”

Some 14,3000 students are now enrolled at Ferris State University.

Although there was no immediate teaching position available for young Ferris, he was able to convince one of the local district officials to let him have a “trial” appointment at a rural common school with a reputation for driving teachers out in short order. Although Ferris managed to survive his first year of teaching, he realized that he lacked the skills needed to become a more effective educator. In April 1870, he sought additional educational training at the Owego Academy. Before he could be admitted, he was required to take an entrance examination.

Ferris wrote in his diary, “I secured sufficient credits to be eligible for admission without examination to Cornell University.” But he did not attend Cornell University, which had accepted its first class of 412 undergraduates in 1868. Instead, he decided to attend the Oswego Normal and Training School, now Oswego State University of New York, an even smaller institution, founded in 1861 with nine students.

On February fourteenth, I arrived at Oswego, New York where the next day I entered upon my examination for entrance to the normal school. I was given one half year’s advanced credit on the classical course.

For all he admired [his Oswego] faculty members, Ferris held Sheldon in the highest esteem, thanks to an incident in May 1872. Sheldon had sent for Ferris, then a 19-year-old undergraduate in his third term. Ferris had just returned from the city police headquarters, charged with striking a local youth who insulted him. Dr. Sheldon apparently was aware of the circumstances of the incident and wanted to advise his hot-blooded young charge that he was to ignore future insults and practice a “philosophy of non-resistance.” Ferris responded, “…as gently as I knew how, that my constitution was so organized that I could not follow this advice. I promised to continue minding my own business, but when insulted I should defend myself. Dr. Sheldon smiled and made no further comment.”

In his autobiography Ferris accepted the fact that his offense was serious enough to have “sent him home but for the generosity of the president, Dr. Edward A. Sheldon.”

After two years at Oswego, Ferris’ funds were gone and he had not completed the teacher training course. He took a brief hiatus to earn money on the lecture circuit and in 1873 Ferris completed his training at Oswego and returned to Tioga County as principal of the Spencer Academy. With him was his wife, Helen, whom he had met while attending Oswego Normal School. She taught in the Spencer Academy and became Ferris’ partner when later in his life he founded the Big Rapids (Michigan) Industrial School, forerunner of Ferris State University in 1884 which celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2009.

It would be difficult to overstate Ferris’ accomplishments in the fields of education and politics. There is a story behind each achievement and Ferris’ efforts sometimes met with failure. The Big Rapids Industrial School went bankrupt twice before succeeding as Ferris Industrial School. His early candidacies for political office were not always successful and although he was a popular governor in Michigan, the “Good Grey Governor,” as he was called by his supporters, was defeated for re-election to a third term.

During his lifetime, Ferris overcame many obstacles and experienced a number of “turning points.” The common thread of these events was that each involved opening his access to more education and thus, his story illustrates a uniquely American process that has enabled greater social mobility among its people from the earliest years of the Republic. Perhaps his greatest achievement and legacy continues to affect the lives of thousands of students who are enrolled in the university that bears his name. For that, Dr. Sheldon may be owed a special debt of thanks.

Edward J. Reid, Ed. D., was raised on a farm in Van Etten, less than 10 miles from Woodbridge Ferris’ birthplace. He is an alumnus of SUNY Albany. After 38 years in education, he retired as Superintendent of the Owego Apalachin Central School District.

You might also like

More from Fall/Winter 2011

Upcoming Events

Jan. 1 Nominations due for alumni awards* Jan. 1 Nominations due for Athletic Hall of Fame* Jan. 4 New York City Career Connections* March …

Young Veteran Aims to Pass on Help He Received

He started his adult life homeless, and entered the Army to get a roof over his head. But when U.S. …

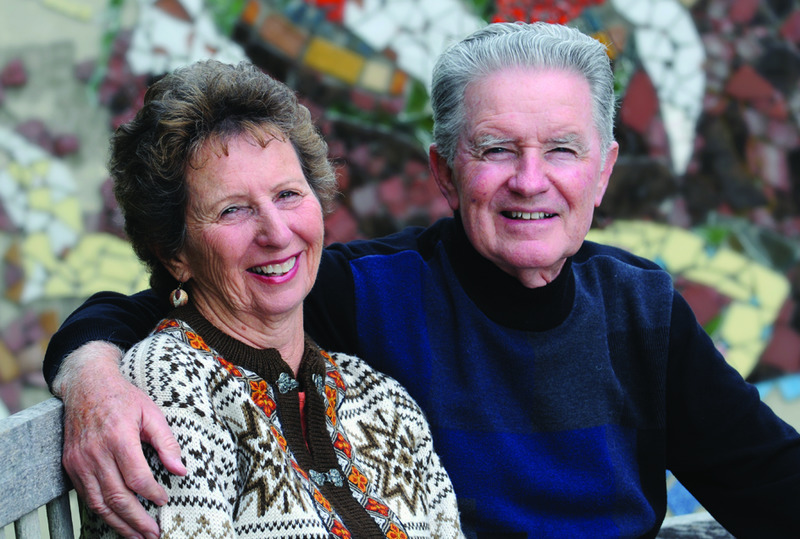

Former Professors Endow Scholarships in Music, Wellness

During their long careers at SUNY Oswego, Hugh and Grace Mowatt Burritt helped thousands of students reach their full potential. …